To understand the present, it always helps to step back and get the bigger picture. Which is why I want to spotlight a recent paper that mines through historical documents for 800 years worth of interest rate data.

In case you’ve missed it, many parts of the world are characterized by negative real interest rates. Investors in 5-year German bonds currently earn -0.6% per year in interest. That’s right. Investors must pay the government for the right to hold a bond for five years.

Compounding the burden of holding a German bond is inflation, which in Europe is expected to register at around 1.5% per year. Inflation eats into the value of a bond’s interest payments and principal. Combining the already negative interest rate with 1.5% inflation means that a German bond investor can expect a total negative return of around -2.1% per year.

Interest rates since 1311

On the face of it, a -2.1% return seems thoroughly outlandish. But in a recent Bank of England staff paper, economic historian Paul Schmelzing finds that negative interest rates aren’t that odd.

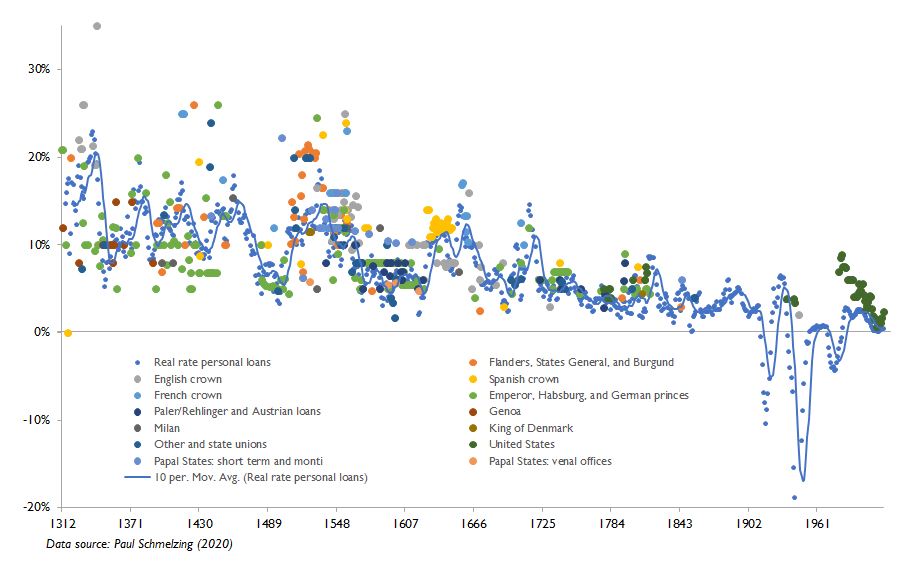

Here is one chart that Schmelzing plots from the data he has collected.

Interest rates on 454 personal/non-marketable loans to sovereigns, 1310-1946, and U.S. EE-series savings bonds (Source: Schmelzing, 2020).

Interest rates on 454 personal/non-marketable loans to sovereigns, 1310-1946, and U.S. EE-series savings bonds (Source: Schmelzing, 2020).It shows interest rates on 454 loans made to sovereigns by court bankers and wealthy merchants.

As the chart illustrates, the real interest rate that lenders have demanded from sovereign borrowers over the last 800 years has been gradually declining. The 0.5% real interest rate

Nor does Schmelzing include loans from Jewish communities in medieval times. These loans often used the threat of expulsion to extract artificially low interest rates.

To adjust the interest rate on loans for inflation, Schmelzing relies on consumer price data compiled by economic historian Robert Allen. Allen’s consumer price index baskets go back to the 14th century. He has constructed them for major cities like London and Milan using old records of items like bread, peat, wood, linen, soap, and candles. Prices are expressed in silver unit equivalents to correct for

Cultural differences are reflected in each city’s respective consumption

- Source, Bullion Star